![]()

ProtoEvo Project

An interactive real-time simulation for evolving multicellular organisms.

Introduction

Evolution is the only process that we know of that can produce the wonderous complexities of the natural world. From ant colonies to nervous systems, from bee waggle-dances to human language. I have had a long standing interest in evolution, but it was intensified in early 2022 when I rewatched Robert Sapolsky’s Human Behavioural Biology lectures and read Neil Shubin’s Some Assembly Required. In particular, my renewed interest was focused on the role of gene regulation in the evolution of complex multicellular systems. Multicellularity is an interesting form of cooperation between individuals, in which their very individuality is given up. But to coordinate this cooperative endeavour, cells take specialised roles in the organism. So I revisted a simulation I start in 2016, during my undergraduate.

The aim of this project is to create an environment where protozoa-like entities evolve their behaviours and morphologies in order to survive and reproduce. The simulation takes place in a 2D environment physically simulated environment.

The project was the subject of a paper that I presented at the ALIFE 2023 conference, and which you can find published in the ALIFE proceedings. If you wish to cite this work, please use the following citation:

Dylan Cope, 2023, “Real-time Evolution of Multicellularity with Artificial Gene Regulation”, in the Proceedings of the 2023 Artificial Life Conference (ALIFE 23), pp. 77-86, MIT Press.

@proceedings{cope2023multicellularity,

author = {Cope, Dylan},

title = {Real-time Evolution of Multicellularity with Artificial Gene Regulation},

booktitle = {Proceedings of the 2023 Artificial Life Conference (ALIFE 23)},

pages = {77-86},

year = {2023},

doi = {10.1162/isal_a_00690}

}

Find the project on GitHub.

For the previous version of the simulation I created a YouTube video that explains the project in more detail. Many of the mechanics have changed since then, but the video still provides a good overview of the project. You can also come and discuss the project on discord!

Simulation Overview

Feeding and the Environment

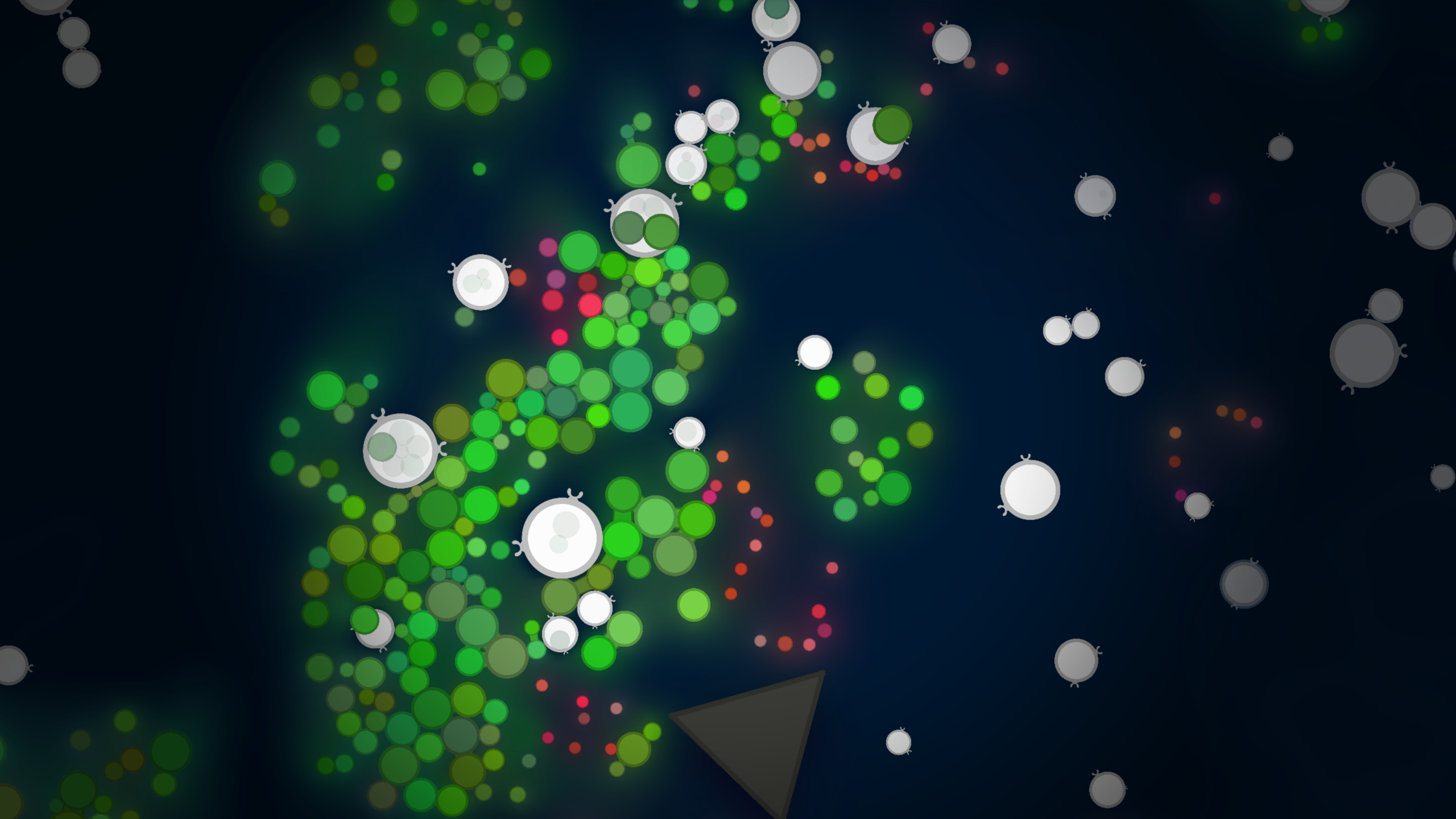

In the following screenshot we can see the protozoa as white circles, and the plants as green circles. The plants emit chemical pheromones that spread through the environment, which provide nutrients and can be detected by the protozoa. The red cells are dead cells that emit nutrients and are rich in resources for the protozoa to feed on. The protozoa can all feed on cells by engulfing them, a process in real cellular biology call phagocytosis.

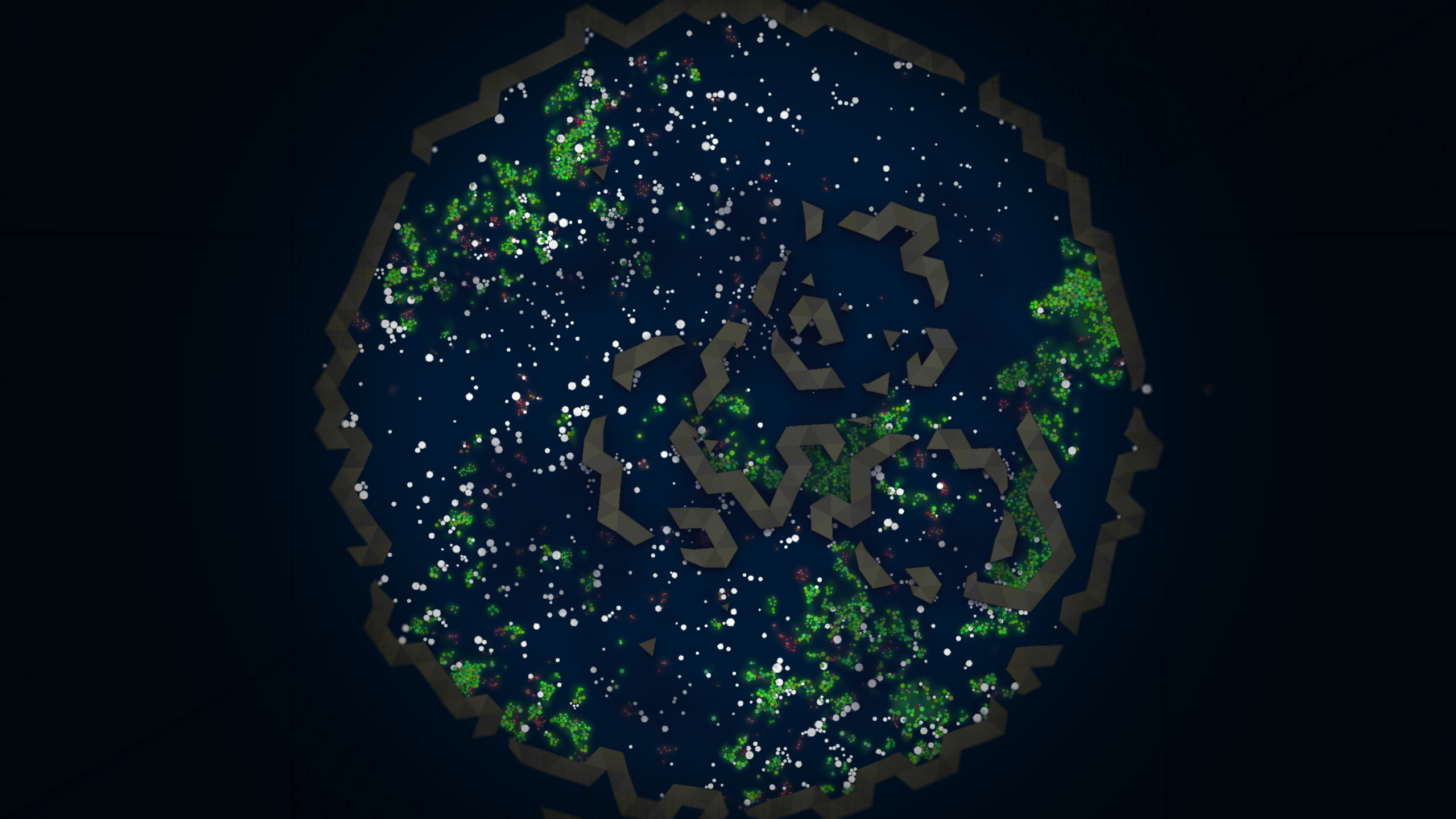

In the above screenshot we also see a brown triangle. This is a “rock”; a rigid body that forms a procedurally generate boundaries in the environment. The next screenshot below shows a more zoomed-out view of the environment, where we can see the rocks forming a boundary around the environment. Outside the outer ring of rocks is a “void” in which there are no resources, and the cold, dark environment is inhospitable to life.

Evolving Multicellularity

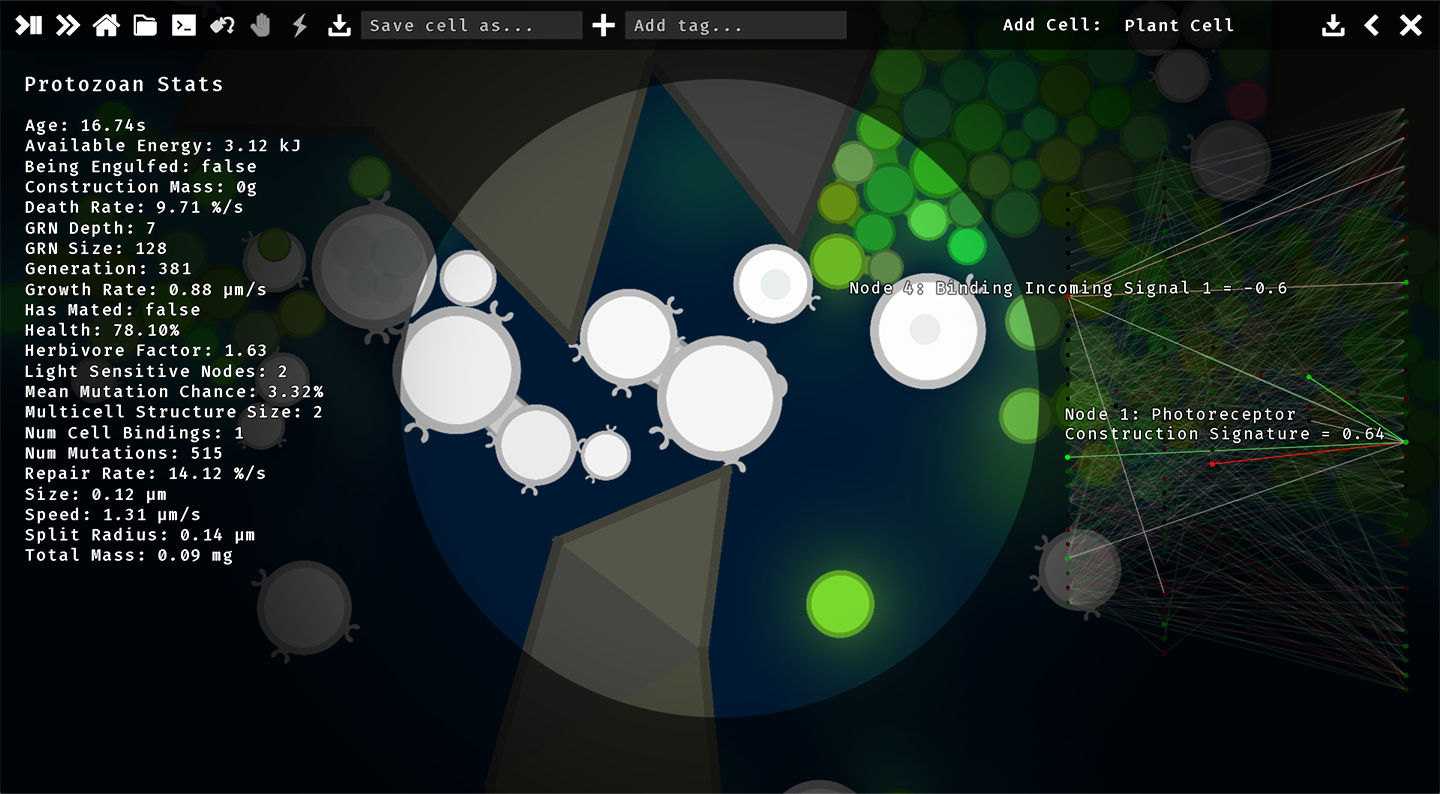

The primary research objective of this project is to investigate the emergence of multicellular structures, i.e. the development of coordinated groups of attached cells that incur a survival benefit by being attached. Further, we are interested in the emergence of cell differentiation, i.e. the development of cells that specialise in different functions. For example, some cells may specialise in feeding, while others may specialise in being light-sensitive, or in reproduction. The following screenshot shows a multicellular structure that has evolved in the simulation. The two cells are bound together and are able to transmit signals to one another. These signals are used to coordinate the feeding behaviour of the two cells, but they also regulate the development of functions. For example, the cell on the right has developed a light-sensitive functions, whereas the cell on the left has only developed feeding function (called phagocytosis nodes).

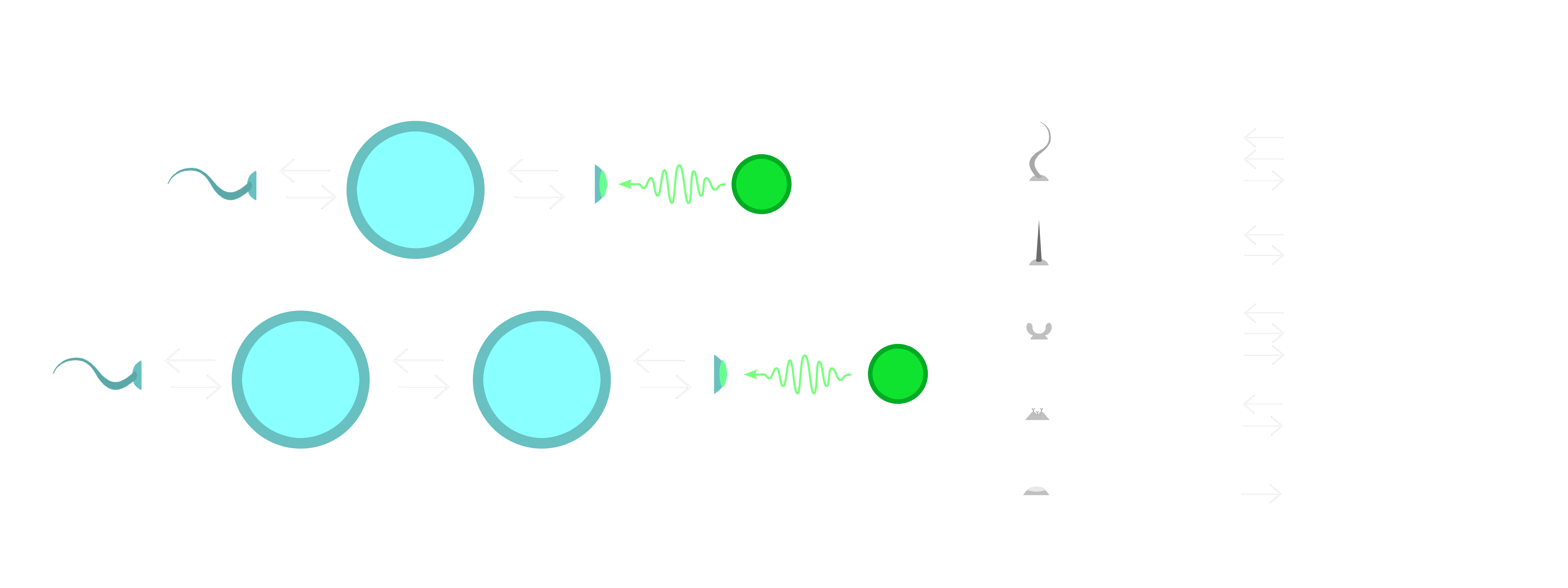

The cell functions are implemented using a “surface node” system and a “fuzzy lock-and-key” mechanism to incorporate signals from a gene regulatory network (GRN) with requirements needed to create the functions. The following diagram illustrates the surface node system with the kinds of nodes that can be constructed by a cell.

The diagram also shows part of the motivation for the surface node system in terms of the kinds of evolutionary dynamics that we hope to observe. This is inspired by what the Evolutionary Biologist Neil Shubin calls “Revolutionary Repurposing” in his book “Some Assembly Required”. The basic idea is that the evolution of new functions is not necessarily a process of creating new genes, but rather can be a process of repurposing existing genes. Putting them into new contexts and combining them in new ways. The surface node system is designed to facilitate this kind of evolutionary process by providing common I/O interfaces for the cell functions. A cell could evolve mechanisms to interpret information from a photoreceptor node, for example, and use that information to regulate the behaviour of a flagellum node. Then, by mutation of the flagellum into a cell adhesion node, the information that was previously used to control movement could be sent to another cell. This could be used to coordinate the behaviour of a group of cells, or to send a signal to another cell to trigger a response.

Resource Flows

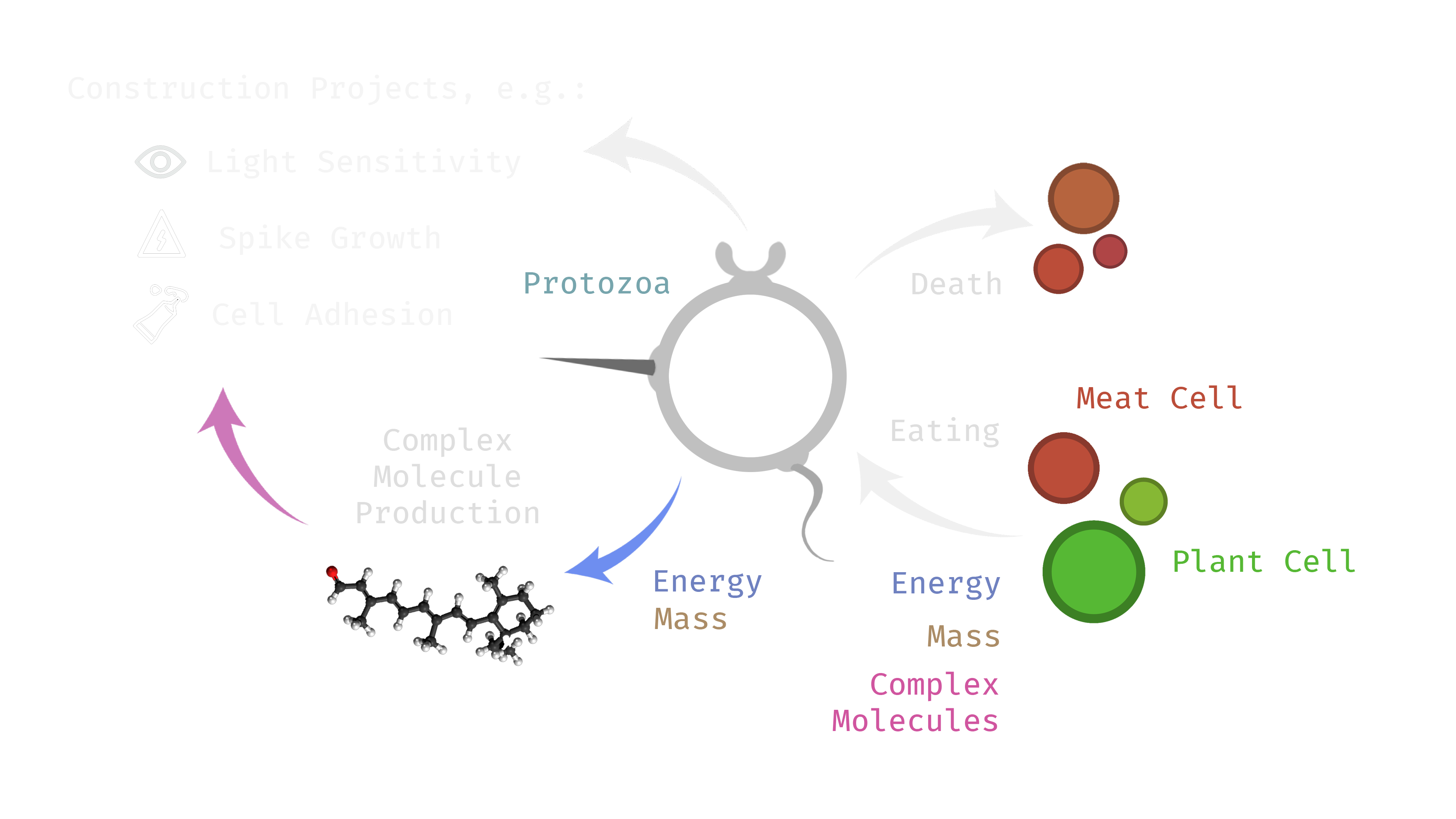

The following diagram shows the resource flows in the simulation. It highlights the importance of something in the simulation called complex molecules. These serve as prerequisites for constructing various traits. They are represented by a number in the unit interval called the molecule’s signature. The simulation only permits a finite number of possible molecules, represented at evenly spaced intervals between 0 and 1. Complex molecules are produced using mass and energy according to a ‘production cost‘ in terms of energy expended per unit of mass produced. The term ‘complex molecules’ is inspired by the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology, that states: “DNA codes for RNA, and RNA codes for proteins”. Complex molecules in the simulation are designed to be analogous to proteins in the following ways; firstly, they are what ultimately implement functions in a cell. Secondly, they are involved in ‘lock-and- key’ mechanisms that act as conditional switches. Thirdly, the choice of which complex molecules are produced is made by the gene regulatory network.

The primary sources of mass and energy in simulation are the plant cells. Plants are ingested by protozoan cells and converted into the stores of available energy and construction mass. Next there are a number of different directions these resources can flow; energy can be converted into action (e.g. in the form of movement). Mass and energy can be used to increase the cell’s supply of complex molecules to be used for later construction projects. Such projects themselves will also require further construction mass and energy on top of the initial investment into the complex molecules. As mentioned before, upon a protozoan’s death its supply of resources is distributed to meat cells spawned in its wake. This includes energy storage, construction mass, and complex molecules. The resources can then be reclaimed by other protozoans that ingest the meat. Meat is denser in energy than plant cells, and they present the potential to skip producing any stored complex molecules.